[Content Warning: body horror and drug use]

If you want to tell the truth, best to do so in a story, and when these truths are dark, best to do so through a work of horror.

Horror is most powerful when it reveals a larger truth about the world we live in. Tackling the devastation of our current opioid crisis is no different. Citing statistics about the number of people who have died from overdoses hardly has the same impact as the tale of one who has suffered. To hear about the nature of addiction in a story, putting the reader into the addict’s body, brain, and spirit as it morphs into something unrecognizable, something horrific, makes the larger crisis much more personal. In this way, horror facilitates understanding, empathy, and even compassion.

Memoir is the primary delivery method of addiction stories, but even in memoir, it is the moments of personal terror we feel most deeply. When horror tackles the subject of addiction, it becomes ultra-realism or a sort of black magic realism, I’ll call it.

Consider Stephen King’s story “Grey Matter,” the powerful tale of a boy catering to his father’s ever-growing alcoholism through buying beer at the local party store and delivering it home for his dad to drink. The child is a hostage in many ways, forced to fuel his father’s habit even as the addiction devours him. We feel such empathy for the child, but if his father never turns into a subhuman, insidious blob multiplying in size as it consumes others, we would not feel the same dread on such a cosmic scale.

This same blob is currently attacking our country. We are living within Stephen King’s “Grey Matter,” but with opioids feeding the beast. On average over 130 people will overdose and die today from opioids. During weekends when overdoses spikes, morgues are overrun in some cities and refrigerated trailers have to be brought in to handle the demand.

The horror genre and speculative fiction is quite often the mirror for this slaughter.

Addiction as horror in film is nothing new, and often presents as body horror or possession. The heroin addict in Saw must rip open the stomach of a human lying next to her in order to save herself from a reverse bear trap. She is one of the few to survive Jigsaw’s torturous puzzles and becomes an advocate of his methods, citing their extreme measure as the only thing that saved her.

Is this what it takes to stop a heroin addiction?

The body horror of addiction can be found in the Evil Dead (2013 version) where the cabin in the woods becomes the refuge of Mia, a heroin addict looking for a place to detox. As the withdrawals hit, the possession begins. Her body becomes ravaged by trees in the forest, is sizzled by a blistering hot shower, and her very arm where she used to inject gets slowly torn from her body at the end.

This is what addiction and then detox feels like—being spiritually occupied and living through a painful mutation of your physical self. To depict this suffering without the element of the horrific or supernatural would be to create a lesser beast, certainly with less verity.

Heroin addiction in the Netflix version of The Haunting of Hill House is perhaps the biggest demonic presence for the Crain family. Director Mike Flanagan took the concept that it’s not houses that are haunted, it’s people that are haunted, and wrapped it up into Luke’s heroin addiction. It becomes a supernatural battle, and, similar to Hereditary, the genre of horror uniquely puts its audience inside the fractured Crain family—the tension, the anger, the cold isolation—just ordinary people dealing with extraordinary demons such as heroin.

The entire Hill House series ends (spoiler alert) with a shot of Luke blowing out a candle celebrating 2 years of being clean, but the possible interpretation that this haunting is not over. The cake, the central object of the scene, is the same color red as the most insidious room of the house—the red room— with a propensity for deluding those inside. We’re left wondering if they are still trapped, deluded with fantasies that such curses can ever be conquered. Luke’s heroin addiction becomes the perfect trope for a person who is haunted by the memories of their misdeeds and by the insatiable urge to use, and this does not end until the final candle goes out.

Compared to these interpersonal conflicts, science fiction often portrays addiction in more cosmic and political tones. In Brave New World, Soma is provided by the government and is the literal opiate of the masses, providing a constant source of bliss, solace, and comfort and stops the population from directing their dissatisfaction toward the state. It’s the drug use of Soma itself that gives the word “brave” in the title its irony.

In the sci-fi land of Dune, water is precious, but it is secondary to the drug, mélange. As Duke Leto Atreides notes, of every valuable commodity known to mankind, “all fades before mélange.” In order to mine and harvest the drug, battles are fought with giant sand worms who move like whales below the surface, all for the wealth of mélange which acts as a hallucinogen, expanding one’s senses and allowing transcendent knowledge and cosmic travel. The horror of addiction remains for withdrawal from mélange is deadly.

While less cosmic, the psychological personal terror of substance D in Phillip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly also finds its roots in dystopian Los Angeles. The war on drugs has been lost, 20% of the population is addicted, and undercover narcotic agent Bob Arctor is addicted to the very drug he is investigating, but not fully aware, for substance D splits the psyche. He ends up in terrible withdrawals, and at the end finds comfort detoxing in a farming commune called New-Path, but in the closing scene, one last absurd truth is revealed. New-Path is growing the very plants used to make substance D. The treatment is also creating fuel for the disease.

One cannot help but think of big pharma, which has been creating opiate addiction en masse, but also profiting from the cure. Narcan is a life-saving pharmaceutical for opioid overdose and appearing on the utility belt of every first responder in the country (and rightly so) but we’ve found ourselves where the pharmaceutical industry profits from the insatiable need for opiates they helped create, but also profiting from the cure.

We’re living inside A Scanner Darkly, living in a Brave New World, and the blob of “Grey Matter” is being fed daily and growing larger.

Horror speaks to this trauma in a more personal fashion, and this seems essential. What better way to capture the epidemic of addiction, and the barren emotional and spiritual states that come with it, than through a work of horror? Until you’ve had your mind and soul hijacked by addiction, it’s difficult to comprehend, for in the throes of a craving, the desire to obtain and use substances equals the life force for survival itself. Imagine yourself drowning and being told not to swim to the surface for air. Obsessions should be so mild.

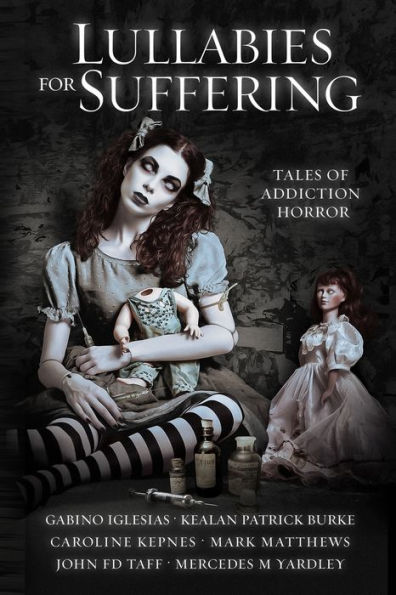

Buy the Book

Lullabies for Suffering

The craving for a substance is not much different than that of a vampire who craves blood. The vampire trope is of the most fluid in horror, so ripe with interpretive innuendoes it often reflects the time the art was made, but one thing that remains consistent is the physical nature of vampires matches that of an addict. They must stay hidden in the shadows to exist, a perpetually cold craving in their gut that is never satisfied. Best they can hope for is a momentary relief from suffering, until the emptiness returns and demands to be filled yet again. The concept of heroin addicts saving milk-blood to keep from running out—saving some heroin-infused blood to inject at a later date—is a term made famous by Neil Young in his song, “The Damage Done”, but seems as if it could be pulled directly from HBO’s horror series True Blood.

By creating such monsters in fiction, the reader is granted understanding of what it is like to live with this affliction, and the compassion for addicts grows. Horror can do that. It does do that. “Horror is not about extreme sadism, it’s about extreme empathy,” Joe Hill so aptly noted in Heart-Shaped Box. Portraying addiction as metaphorical monster, such as vampirism, the physical, or possession, the spiritual, demonstrates the type of biological and spiritual forces addicts are fighting against. Being understood means feeling less alone, and there is infinite power in ending that isolation. There is a reason the 12 steps of AA start with the word We. The compassion and power of being understood by a group has tremendous healing, and ending the isolation is often the beginning of one’s recovery.

I’ve been in recovery for 25 years, but I still feel the addiction inside me, speaking to me. My mouth waters when I think of vodka. I feel an electric jolt down my spine when I see someone snorting cocaine in a movie. In this way, like Luke Crain of Hill House, like Mia from the Evil Dead, recovering addicts such as myself remain possessed, and what is more horrific than that?

Yet at the same time, what testament to the human spirit that the desire for health and wholeness can battle such demons and win, learn how to diffuse the cravings, and squeeze unprecedented joy out of life. Right now someone just picked up their 60-day token, someone is blowing out the candle on a cake celebrating 3 years of sobriety. Loved ones witness this transformation of this miracle as if watching someone lost rise from the grave.

I’ve been writing about my addiction for years, for when I open up a vein, this is what spills upon the page. My last two efforts were an invitation for other writers to explore “addiction horror.” The results are the anthologies Garden of Fiends and the new Lullabies for Suffering, pieces of fiction that demand work from very intimate places from each writer’s heart. As Josh Malerman said of these tales of addiction horror; “What fertile ground for horror. Every topic comes from a dark, personal place.”

Horror can shine a blinding light into the eyes of these demons, these dark truths of addiction, in a way no other genre can. It allows the fiction to scream events that are true, even if they never happened. In this way, the darkness of horror, even in its most grotesque forms, leads to a deeper understanding, and during its best moments, compassion and empathy for the sick and suffering addict.

Mark Matthews is a graduate of the University of Michigan and a licensed professional counselor who has worked in behavioral health for over 20 years. He is the author of On the Lips of Children, All Smoke Rises, and Milk-Blood, as well as the editor of Lullabies for Suffering and Garden of Fiends: Tales of Addiction Horror. He lives near Detroit with his wife and two daughters. Reach him at [email protected]